The full range of modern Muslim intellectuals is wide. It inevitably includes Islamist thinkers, some of whom have embraced violence at some point in their lives. Today’s post-9/11 culture reduces these Islamists to caricatures of anti-Western fanaticism–to different versions of Osama Bin laden, et al. I argue in the following piece that their legacy deserves a much closer examination.

Published by the Los Angeles Review of Books on August 4th, 2017

On the morning of September 16th, 1920, a horse-drawn carriage pulled up in front JP Morgan Bank on 23 Wall Street, right at the heart of Manhattan’s financial district. Inside the wagon sat about 100 pounds of dynamite and 500 pounds of cast-iron weights, all hitched to a timer-set detonator. By noon, a vicious blast ripped through the surrounding area, resulting in 40 deaths and hundreds injured. It was, as author and historian Mike Davis observes, modern society’s first introduction to “the prototype car bomb.”

This infamous attack, dubbed the “Wall Street Bombing,” was at that point the worst instance of domestic terrorism in United States history. Though the perpetrators of the explosion were never apprehended, authorities strongly suspected that violent anarchist activists had carried it out. More specifically, they suspected the Galleanists, a strain of “propaganda of the deed” anarchists who followed the works of Luigi Galleani, a leading Italian-American anarchist thinker who preached the overthrow of capitalism and government by violent means. It was the Galleanists who, along with some other anarchists, carried out a string of similar attacks across the US in 1919.

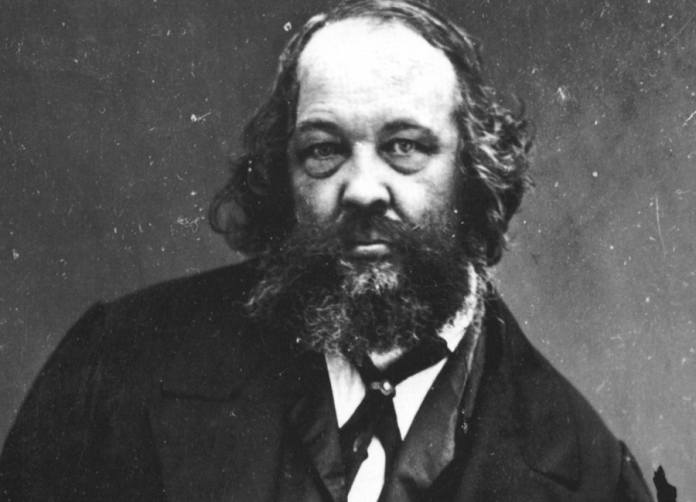

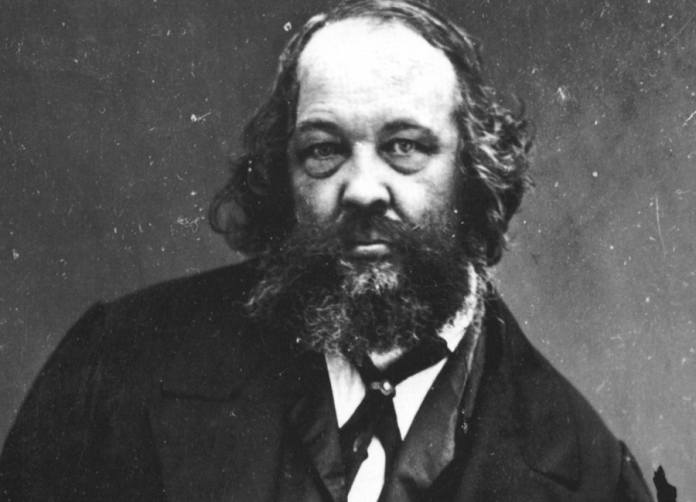

The phrase “propaganda of the deed” is now used to refer to a whole family of political actions that, by way of posing as often-violent examples to the rest of society, can theoretically act as a catalyst for wider revolution. They can, as Galleani notes in his 1925 book The End of Anarchism?, “kindle in the minds of the proletariat the flame of the idea” of a more egalitarian world and thus lead to “vigorous preparation for the armed insurrection.” The phrase itself was coined in the 19th century by the Russian writer Mikhail Bakunin, a leading anarchist thinker of his time, a rival of Karl Marx, and a now a mostly forgotten figure.

Mikhail Bakunin

In his 1870 “Letters to a Frenchman on the Present Crisis,” Bakunin writes, “All of us must now embark on stormy revolutionary seas, and from this very moment we must spread our principles, not with words but with deeds, for this is the most popular, the most potent, and the most irresistible form of propaganda.”

Of course, “propaganda of the deed” doesn’t necessarily have to involve dynamite, bloodshed, and death, but the anarchist movement of that era was characterized most famously by instances like the 1919 Galleanist bombings or the assassination of high profile politicians like US President William McKinley (1901). Such acts shocked the Western world at a time when millions of people were experiencing the effects of systemic social and economic transformation via the industrial revolution and the rise of modern global capitalism.

Works by figures like Bakunin, Marx and numerous others were responding to seismic social changes, but it was Bakunin who never stopped preaching violent revolt as the primary agent of historical progress. He openly called for the violent overthrow of existing orders, such as the Hapsburg Monarchy, as a way to achieve true egalitarian progress.

It’s a curious but useful exercise to look back and ponder proponents of political violence like Bakunin, particularly as Western Europe reels from one terrorist attack after another and as the so called “Islamic State” (ISIS) remains in control of a sizeable piece of territory in Syria and Iraq. The 9/11 attacks ushered in the Era of National Security, an almost mandatory lens through which to look at the times. According to subsequent piles of “anti-terror” legislation, even verbal or cyber expressions in favor of violence can potentially amount to “material support” for (mostly Islamist) terrorism, a major crime.

Despite this paranoia, the world today is usually capacious and patient enough to place and assess problematic figures like Bakunin within the wider social and historical contexts of 19th century political unrest. Bukanin, a consistent and fierce preacher of violent sociopolitical change, is still read and studied, though not so widely these days, in post-secondary seminars, along with other figures whose proposals throughout the centuries echo the violent extremism that has worked its way into much of the world today—sometimes with an Islamist colouring, sometimes not.

But unlike the violence of Bakunin’s time, today’s terrorism is subject to a whole new matrix of pseudo-empirical and quantitative analysis: from counter-terrorism studies to “ideological detox” to deradicalization clinics to the implementation of social engineering schemes like local CVE programs.

But unlike the violence of Bakunin’s time, today’s “Islamic terrorism” is subject to a whole post-9/11 matrix of pseudo-empirical and quantitative analysis: from counter-terrorism studies to “ideological detox” to deradicalization clinics to the implementation of social engineering schemes like local CVE programs. The ideas and ideologies associated with “Islamic terrorism” are then fed through this apparatus and analyzed with an immediacy that favors the ill-defined parameters and mandate of “security studies.”

Each Muslim thinker or promoter of extremism (even those who died long before 9/11) is shrunk down and associated first-and-foremost with recent acts of violence. In other words, the first reaction to such historical figures isn’t—as in the case of Bakunin and others—to view them as a lens into history, but rather to situate them within a present-day “security” context as a possible (even imminent) threat from the past. This is a direct reflection of today’s tendency to perceive and evaluate Muslims not as flesh-and-blood human beings, but as units of ideological action.

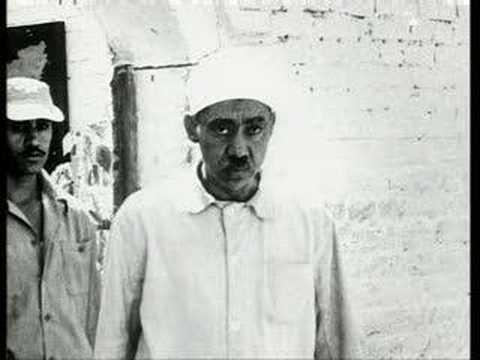

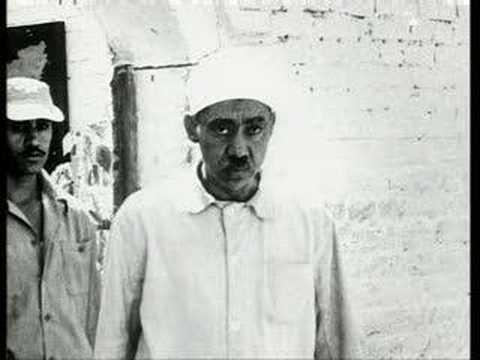

Sayyid Qutb and Islamism of the deed

Many Islamist thinkers have suggested violence as a way of bringing about utopia. They differ as much in ideology as they do in intellectual substance. But the one figure whose profile has risen most recently and infamously as the quintessential “philosopher of Islamic terror” is the late Egyptian author, theologian, and eventual agitator Sayyid Qutb, who died almost four decades before 9/11.

Analysts and observers from Paul Berman to Lawrence Wright have referred to Qutb, whose writings and activism in Egypt during the 1960s eventually led to his execution by Gamal Abdel Nasser’s regime in 1966, as the godfather of Islamic terrorism. It should be noted that such terrorism varies widely in tactical form and strategic purpose, while spanning the gamut of many different groups and nationalities. Their overall modus operandi, though buttressed by a different set of ideas and used for a different set of goals, bear the same kind of “revolutionary” imprimatur of, say, the Galleanist bombings a century earlier. Generally speaking, these are actions perpetrated as a form of violent propaganda (of the deed).

Sayyid Qutb in prison

Yet the way we understand and approach the intellectual figures behind today’s displays of Muslim political violence is much more contingent on the post-9/11 ideological and political climate than most would like to admit. Qutb, for instance, is still associated with the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood (though he eventually abandoned them for a more radical path), perhaps the most famous Islamist organization in the world. The Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party won a popular mandate to govern Egypt after the 2011 fall of Hosni Mubarak and before a military coup forced them underground two years later. Today, for a number of political reasons, the Trump administration is considering putting the Muslim Brotherhood on the US list of terrorist organizations, alongside groups like Al-Qaeda, which has been on the list since 1999.

Detractors of the Brotherhood point to its historical association with Qutb as Exhibit A of the organization’s hidden “radical Islamist” agenda and silent support for terrorism, even though the group publicly renounced violence in the 1970s. This treatment of Qutb is characteristic of the post-9/11 West’s tendency to eschew a more nuanced engagement with pro-violence Islamist thinkers in favor of a more security-centric approach.

Detractors of the Brotherhood point to its historical association with Qutb as Exhibit A of the organization’s hidden “radical Islamist” agenda and silent support for terrorism, even though the group publicly renounced violence in the 1970s.

This is as true of liberal observers and writers as it is of neo-conservatives. Whereas hawkish voices on the American right such as the Foundation for Defense of Democracies are happy to name Qutb as a “prominent MB ideologue” and a figure that Al Qaeda has cited from time to time, more liberal voices such as Paul Berman are equally happy to point Qutb out as the “intellectual hero” of all modern jihadists.

Both of these sweeping assertions lack specificity, accuracy and context, but the larger effect of their collective pronouncements is to reduce Qutb into what can bluntly be called a terrorist thinker. It is true that Qutb’s advocacy of violence had an effect on the likes of Bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri, but that’s not all he was. It is also true that Bakunin’s call for violent revolution influenced anarchist terrorists down the line, but that’s not all he preached or wrote about. Yet whereas current Western culture still has room in the classroom and elsewhere to consider and evaluate Bakunin in all his complexities (while, of course, recognizing the dangers that he represents), post-9/11 attitudes stand in the way of a similar understanding of Qutb and those like him. The demonization of the MB, an imperfect organization with deeply Islamist ideological roots, by some of its lazier critics in the West is a primary example of this intellectual double standard.

Though the MB haven’t renounced Qutb per se, it is a stretch to call him one of the animating forces behind the organization today, as the FDD does in their overview of the group. (Notice also that connection to Qutb also makes it okay to lump the MB together with Al Qaeda.) But Bakunin had a similar degree of impact on many contemporary organizations and movements, such as the anti-globalization movement or anarchist groups like the International Workers of the World (the Wobblies). No serious commentators or policy writers are calling for all self-professed anarchists and anti-globalization activists to be classified as terrorists, even if they share a handful of ideologues (including Bakunin) with more violent groups.

The dog we know vs. the revolutionary we don’t know

A distinction should also be made between figures like Qutb and other, even more relevant ideologues to today’s violence who’ve devoted their entire corpus to the ideologies and tactics of violent jihad. These include outright criminal figures like Abu Musab al-Suri, whose 1600-page work on The Global Islamic Resistance Call popularized the ideas of “leaderless jihad” as a terrorist tactic, along with Abu Bakr Naji, whose Management of Savagery was written as a guide for Al-Qaeda and other Muslim terrorist groups to work towards an “Islamic Caliphate.”

These so called intellectuals don’t work or write outside of the narrow and myopic realm of violent Islamist activism. Their works are devoted wholly to the perpetration of crimes and how to get away with it. Their Islamic knowledge is often cursory at best and bears no resemblance to any sort of traditional learning that has constituted the backbone of the normative Islamic tradition for over a thousand years. In other words, engaging with these “scholars” would be analogous to looking through something like The Anarchists’ Cookbook to gain any kind of understanding of Bakunin or Peter Kropotkin.

Abu Musab al-Suri

Unlike al-Suri or Naji, Qutb is indeed more akin to Bakunin, who had a lot more to say about the world’s machinations than how to kill people for ideological or social reasons. Qutb and Bakunin’s arguments for the usage of violence is situated in a larger, often sophisticated scheme or vision of how society must be changed and dealt with in relation to justice and other ideals. Qutb’s major works, like his multi-volume In the Shade of the Quran, are often regarded as highly important accomplishment in Islamic exegesis. And if it weren’t for his self-important and, quite honestly, rather monotonous screeds on the “obligatory” duties of killing the infidels (his Milestones, written in and smuggled out of prison, is a kind of personal manifesto for Islamist-based violence), Qutb would’ve secured a place in the mainstream pantheon of modern Muslim thinkers.

Karl Marx is another, perhaps even more illuminating example for analogy. In an article for the November 6th edition of the Neue Rheinische Zeitung in 1848, Marx famously concluded “that there is only one way in which the murderous death agonies of the old society and the bloody birth throes of the new society can be shortened, simplified and concentrated, and that way is revolutionary terror.”

Islamists come from a different world outside of “the West.” They represent “the dog we don’t know,” and are thus full of mysterious and opaque danger, as the catastrophic events of 9/11 apparently demonstrate. So they must endure a different sort of judgement.

Of course, Marx never wrote any practical manuals about the tactical aspects of this “revolutionary terror” ala al-Suri or Naji, but he was certainly referring to his own version of a wider “jihad” that would overtake society so as to catalyze revolutionary change in Europe and beyond. It fell on others down the line to interpret Marxist ideas into action by way of more violent tactics such as guerrilla warfare. Among such interpreters are Mao Zedong, whose On Guerrilla Warfare influenced a generation of strategists–including Che Guevara, who wrote his own book on the subject right after the Cuban Revolution. But even Mao and Che, two figures who had no problem with applying violence to realize certain political ends, enjoy a more nuanced reception today in contrast to Islamist figures who flirted with violent ideas. Che has been the subject of a two-part Hollywood biopic by Steven Soderbergh while Mao, though widely recognized today as a political monster, has been extensively studied in all his aspects.

This discrepancy exists because Marx, regardless of his rhetoric or ideas, is a known commodity of sorts, as is Bakunin (though less so). They are the known revolutionaries whose place in Western history has been studied and taken into account. Islamists come from a different world outside of “the West.” They represent “the dog we don’t know,” and are thus full of mysterious and opaque danger, as the catastrophic events of 9/11 apparently demonstrate. So they must endure a different sort of judgement.

Marx’s bloody rhetoric, along with Bakunin’s preaching of violent revolutionary necessities, is the kind of theorizing that can be found in some of Qutb’s work, albeit in light of a very different set of sociopolitical circumstances. But because of today’s post-9/11 hang-ups, it’s almost always the Islamist thinker who gets singled out as especially dangerous, a reputation that taints any person or group affiliated with him in any way.

Karl Marx

In significant parts of Western culture today—particularly in Canada and Western Europe if not also the US—there are communist and Marxist societies/parties/groups lingering in almost every corner—from university campuses to actual electoral parties—that take the ideas of Marxist theory into the political and public sphere, all without much fear of being put on the US State Department’s list of banned terrorist entities. These groups often bear the very name of a man who, over a hundred years ago, advocated for violent means of revolutionary change.

To be sure, there are also Marxist or anarchist groups who’ve rightfully earned their spot on whatever list of banned entities long before the paranoia of the post-9/11 age, but they are in the minority and usually bear a long and prolific history of violent activities. The wider society knows not to center groups like the Revolutionary Armed Forced (FARC) of Colombia or the Tamil Tigers (LTTE) of Sri Lanka when engaging with the larger ideas of Marx, who deservedly remains one of the most influential and quoted figures in Western social sciences and humanities. Yet such conflations are made regularly today, as the reasons for 9/11 and the like are traced back to Qutb.

Those with a better understanding of Qutb, like Muqtader Khan of the University of Delaware, who’s taken the time to peruse through the thinker’s works, are largely confined to academia and thus overwhelmed by post-9/11 trends of reductive securitization.

Those with a better understanding of Qutb, like Muqtader Khan of the University of Delaware, who’s taken the time to peruse through the thinker’s works, are largely confined to academia and thus overwhelmed by post-9/11 trends of reductive securitization. Scholars like Khan have written about the wider range and implications of Qutb’s political and theological ideas, but the more nuanced picture they paint is often lost among the cacophony of post-9/11 chaos.

So for Qutb, along with other Islamist thinkers like Hassan al-Banna, who founded the Muslim Brotherhood in 1928, or his Pakistani counterpart Syed Abul A’la Maududi, there is a different set of rules at play. They are assessed first and foremost with respect to what they’ve said or done about violence. Their wider ideas are placed aside indefinitely if any of their history bears an association to Islamist bloodshed. And any organizations or groups, like the Muslim Brotherhood for example, that are associated with them, must then bear the same stain—public renouncements of violence be damned.

It goes without saying that concerns and questions pertaining to security and safety are important. But these are questions that bear an immediacy that’s better applied to living criminal masterminds like al-Suri, whose ideas centre particularly on the application of terrorism as a way to engender social change and who has been connected to post-9/11 acts of violence like the 2004 Madrid train bombing. Such figures deserve to be assessed that way because, unlike the long-dead Qutb, they are a living and breathing security threat, which is why authorities captured al-Suri via “extraordinary rendition” in Pakistan in 2005. He’s now languishing in a Syrian prison.

Where too much credit isn’t due

The first chapter of Lawrence Wright’s The Looming Tower contains an illuminating passage of how Ayman al-Zawahiri, then Al-Qaeda’s second in command after Bin Laden, mused about extending the ideas of Qutb’s call for jihad into violent practise. It is a pretty damning piece of evidence with regards to the implications of Qutb’s ideas and visions for jihadism. According to the same chapter in Wright’s book, Qutb was offered a way out of prison and execution in his last years by Nasser (who even offered Qutb a spot in his cabinet), but preferred “martyrdom” at the hands of a state he was trying to destabilize.

This ideological connection between al-Zawahiri and Qutb is supposed to illustrate the firm continuation of violent jihadism from thinker to doer, much like how Luigi Galleani’s ideas were carried out by whoever placed dynamite inside of that horse carriage in front of JP Morgan. The implication of such a connection extends beyond al-Zawahiri himself and depicts Qutb as the original inspiration of every other jihadist group, from ISIS to the Nusra Front to Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and so on.

Such a one-dimensional portrayal of Qutb has become commonplace in the post-9/11 age and helps to cement his reputation first and foremost as a violent Islamist.

Fighters of the Islamic State (or ISIS) in Raqqa, Syria

Along with Wright’s book, filmmaker Adam Curtis’ noted three-part documentary series The Power of Nightmares (2004) also features a portrayal of Qutb’s radicalization that follows essentially the same rubric. Curtis juxtaposes Qutb with the neoconservative political theorist Leo Strauss while depicting the two figures as historical and political parallels—each eventually pointing to the other’s ideological legacy as a bogeyman, a dialectical process that, according to Curtis, forms the basis of today’s climate of paranoia and fear.

It must be pointed out that, again, it is precisely such portrayals of figures like Qutb as mindless fanatics that take one out of history’s complexities. Regardless of how right Curtis or Wright are in their diagnoses of Qutb’s pro-violence arguments, the bigger picture remains hidden. Qutb, like Bakunin and Marx, had much more to say. He was, for example, a celebrated literary critic who helped popularize the stories of Egypt’s eventual Nobel Prize Laureate Naguib Mahfouz. Qutb also wrote novels himself and was a noted poet. His more political and radical works followed life experiences that convinced him of modernity’s corrupting influences, thus necessitating in his mind the emergence of an Islamic vanguard to lead the world, through violence, to an all-encompassing embrace of Islamic principles.

This is a rather Leninist and obviously problematic vision that comes out of a post-colonial experience with modernity. It also facilitates the transformation of Islam, a complex and wide-ranging faith with a deep history, into a shopping list of political tasks. But it’s this dislocating ideological background within which Qutb’s call for violence is situated. The only way to truly understand present day extremism in light of this aspect of the past is to engage with Qutb in his entirety. That means moving away from reductive and inaccurate frameworks that depict him as the ideological source of today’s terrorism.

How radicalized groups come about are contingent only partially on ideas alone, and at least equally on other political factors that have to do with post-revolutionary vacuums (as in the case of the Arab Spring) or perceived grievances.

Terrorism is a tactic that’s been around since ancient times. How radicalized groups come about are contingent only partially on ideas alone, and at least equally on other political factors that have to do with post-revolutionary vacuums (as in the case of the Arab Spring) or perceived grievances. Ideas and ideologies are important, but they’re hardly the only drivers of someone’s path to violence.

Years of studies regarding radicalization haven’t even pinned down ideas alone as the most important or pervasive driver of violent behaviour for each extremist. It’s true that ideas matter the most for some, but not for others. Yet the present post-9/11 culture focuses on these ideologies as a function of religious belief, thus pushing a “securitizing” effect onto complicated figures like Qutb, a small portion of whose works can be dangerously influential, but whose hypothetical non-existence probably wouldn’t have stemmed the tide of violent Muslim extremism as a social and political phenomenon altogether. In other words, had Qutb never been born, catastrophic events like 9/11 or something else of such a magnitude would likely still have occurred.

Attributing the beginnings of all violent Muslim extremism to the pages of Qutb’s work is akin to attributing the actions and crimes of the Tamil Tigers to Marx’s 1848 article, or anarchist bombings to the pages of Bakunin. Such a reductive tendency with regards to violent Islamism is one area where today’s neoconservative right has converged with the more liberal center. Knowingly or not, more liberal writers like Wright and Berman often overlap with their right-wing counterparts at neoconservative think tanks like the FDD when they present and depict Islamist theorists in such a one-dimensional way. Both camps refuse to take Muslim thinkers seriously as historical figures who’re substantially captive to their own times and emotions.

Moreover, their thinking extended far beyond violence itself and its application. A fair assessment of who they were and the work they did means taking into account the entire range of ideas for which they advocated.

It is today’s post-9/11, security-obsessed and racist climate that keeps the public from such an engagement with Muslim thinkers. The tendency is to always look for connections between these thinkers and terrorism, hoping that such exercises will contribute to more public safety. But violence is much more complicated. People’s interpretations of ideas and texts are a reflection of their own inner stories and realities, which are often subject to much more than just the ideas of some 19th or early 20th century writer.

Engagement over negligence

Contrary to present-day assumptions, a more open-minded and less ideological assessment of thinkers such as Qutb—rather like that offered to problematic Western thinkers—will actually yield insights that can potentially lead to the kind of understanding that engenders peace and safety. Qutb was certainly radicalized according to today’s standards. But his path to advocating violence occurred at a time in the Muslim world when many were trying with varying degrees of effectiveness to respond to what they saw as the decline of Muslim civilizations. The intellectuals among them (and not all of whom advocated violence!) have produced works and lived lives that offer up very useful windows into how different Muslim societies and countries function today in relation to the wider world.

Violent groups should indeed be banned and their members locked up, but those who promote ideas in a peaceful manner should be dealt with differently, regardless of their association with dead figures who once preached armed struggle against the state. This is why banning groups like the Muslim Brotherhood, which hasn’t perpetrated an act of terrorism for decades and have given up revolutionary means to embrace political gradualism, would be so foolish.

Reading into the works of Bakunin offers an entry into understanding a different time. Engaging with a figure like that makes clear the obvious absurdity of trying to ban every group, violent or otherwise, who take after a radical thinker’s ideas. Violent groups should indeed be banned and their members locked up, but those who promote ideas in a peaceful manner should be dealt with differently, regardless of their tenuous association with dead figures who once preached armed struggle against the state. This is why banning groups like the Muslim Brotherhood, which hasn’t perpetrated an act of terrorism for decades and have given up revolutionary means to embrace political gradualism, would be so foolish. It would be like locking up the members of Greece’s Syriza party because it is a coalition that includes a contingent of Marxist-Leninists.

But people know better than to reflexively conflate Marxist politics or beliefs with illegal and criminal activities. Yet the tenor and pervasiveness of post-9/11 attitudes, rhetoric, and politics has impeded an equal approach to the crop of Muslim thinkers who condone violent change.

Marx and Bakunin believed that only revolutionary violence could eliminate the prevailing cobweb of systemic societal problems. They were certainly wrong on many counts as far as the ethics of violent implementations are concerned. Qutb was no better, but he too was responding to the political circumstances around him, about which he felt deeply disturbed. Combined with the personal effects of how this outside world interacted with his mind, a set of dangerous ideas and prescriptions came into being. Tracing the genealogy of these ideas and placing them in their proper place means engagement. Not censorship or denial. They are ideas to be assessed and grappled with, regardless of whether they come from a violent and disturbed Muslim or not.

[http://marginalia.lareviewofbooks.org/islamist-violence-worse/]

The partners bought this house at 216 Harlandale Avenue in early 2014 as their first property to flip

The partners bought this house at 216 Harlandale Avenue in early 2014 as their first property to flip